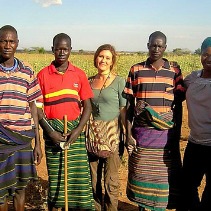

Last week, I had the opportunity to travel with Grace and Patrick of CECORE to Karamoja. They carried out peacebuilding workshops in Moroto and Kotido (more on that to follow) while I met with local NGOs.

Karamoja is a region of northeastern Uganda inhabited by an agro-pastoralist people known collectively as the Karimojong, although this group is actually comprised of several ethnic clans. Karamoja’s history is inseparable from gun violence. Even in the nineteenth century, northeastern Uganda and western Kenya were home to gun markets, and ammunition was used as a regional currency. The Karimojong, who comprise 12% of Uganda’s total population, view the gun as necessary to ensure their safety from cattle raids by rival clans. In Karamoja, cows are king, and cattle rustling (armed raids in which rival clans steal cattle from their opponents) is part of their way of life. The advent of cheap, lightweight guns and the proliferation of small arms resulting from regional insecurity, however, have turned cattle rustling into an especially dangerous endeavor. If you know as little about K’ja as I did when I first came to Uganda, I’d recommend googling the name “Dr. Nene Mburu” to provide a more detailed history of the Karimojong.

The status of Karimojong women is literally lower than that of the cow. Men and women do not sit together, and as Francis Lomongin of FORDIPOM put it, men believe that women “have no brains”. In spite of this, women do all the work both within and outside of the household. Grace Namer of CARITAS describes them as “beasts of burden”. Women gather and transport firewood, tend the crops, cook, construct cattle enclosures, and tend to the children as well. Because cattle herding is left to adolescent boys, the men spend most of their days relaxing and drinking local brews, such as the aptly named “Knockout”. According to Namer and other NGO representatives, it’s best to visit the manyattas in the morning because the men are drunk by mid-afternoon-which proved to be generally true.

Karimojong women are the property of their husbands. Men use cattle to pay a bride price or dowry to a girl’s parents. Once purchased, the husband is free to treat her any way he likes. “He can even kill her,” Namer reports. This abuse starts even before marriage. Many Karimojong engage in a practice referred to as “courtship rape”. When a man decides he wants to marry a woman, he wrestles her to the ground and rapes her. They are then to be wed as soon as he pays for her. The woman has no say in the matter. Many young girls are paired with older men, and if a girl attempts to refuse, she may be beaten by her family or by the relatives of the prospective partner. Polygamy is also common, and a man may “take a wife” as compensation for rape. Because a higher bride price fetches a more desirable partner, men strive to obtain as many cows as possible to offer to the girl’s parents. The need for cows invariably leads to cattle rustling and to a cycle of violence and revenge.

Once married, nearly all women suffer domestic violence. Each of the NGO representatives I spoke with estimated that more than 90% of Karimojong women are beaten. They are beaten if they do not produce enough food, if they burn food, if they eat before their partners, if they refuse sex, if they do not bring in money from the sale of firewood, if their husbands have too much to drink, and the list goes on. Patrick Osekeny of UNFPA recalls a woman telling him, “if he [my husband] doesn’t beat me, then I’m not a woman.”

According to Lomongin, the gun adds to the man’s “aura of power” and helps him to maintain dominance over the woman. During the Disarming Domestic Violence campaign launch, Joe Burua, of the National Focal Point on Small Arms, claimed that Karimojong women are the custodians of the gun, but everyone I asked strongly disagreed with this suggestion. Women do help their husbands hide guns when the soldiers come, but they are certainly not the owners or the users. In fact, the gun is perceived as a symbol of masculinity, and disarmament is equated with impotence. Romano Longole of Kotido Peace Initiative (KOPEIN) claims that the UPDF and police use women to obtain guns. Karimojong men will be arrested arbitrarily and held until the wife produces a gun-whether it actually belongs to her husband or not. Longole asserts that there have been numerous cases of women being beaten by their husbands for turning over the guns. The very concept ofarmed disarmament is a tricky one, especially given the region’s history, but there is no denying the devastating impact that guns continue to have on the Karimojong.

Posted By Courtney Chance

Posted Sep 9th, 2009