Just after arriving in Enoosaen, we visited Mr. Gideon Konchella, the Member of Parliament (MP) for Transmara District (Kakenya’s district). MP’s in Kenya hold enormous power – and a good number use this influence to pad their wallets and hand out favors to friends. Mr. Konchella is different. On the day he was visiting the town near Kakenya’s home, he had a line of men from the area waiting for a moment with him. There must have been one hundred or more of them, pouring out of the waiting room and onto the steps of the building. But this is not unusual; what was quite different was the preference he showed for Kakenya. We were among only a handful of women peppered amongst the crowd, and we waited for only a few minutes before being called into the MP’s office. Mr. Konchella, his face warm and welcoming, was eager to help Kakenya. He has already contribute $15,000 for the construction of her school’s dormitories; during this visit, he offered for his office to manage Kakenya’s funds when she mentioned some of her money had been misappropriated during the school’s construction.

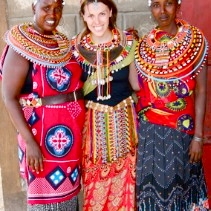

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

We seized on the opportunity to talk to a man in politics who actually advocates for girls education, and here’s what Mr. Konchella had to say:

Kate: Why do you think girls’ education is important in Maasai culture?

MP Mr. Konchella: It is so important because, first of all, girls have been left behind. The process of FGM has been a terrible issue, also, because a girl has to go through this ritual before she is married. And once the child has been schooled and then [goes through FGM], her mental attitude is now I am a woman and now I need to get married.

…The Maasai community has a very unique behavior – they do what they want to do because they’ve seen someone doing it. If you have good cows – a good breed – everyone wants to have that breed because they will have more meat and more milk. So when they see somebody who has a PhD, they say what? What is a PhD? So if she gets a job [pointing now to Kakenya], and she is articulate, then everyone wants their daughters to be like her. So it is a very easy community to transform. Other communities will be different. This is a social community, where people live together…they know each other – they follow the one who is doing better. So that is why I am encouraging education for girls – to transform the community.

K: So if women become educated, what changes will you see in Maasai culture – how will households be different, and families be different?

MP: Certain habits will not be there. Like FGM or being careless about managing a home. Cleanliness, health problems – and educating their own children – it is going to change…we have sent a lot of other people like her [points to Kakenya] to university in other parts of the world and out of that, they are working in the government and in the private sector… each one has put up a stone house, they have a car, and everybody says wow I want to be like them.

Luna: As a father, how did you educate your daughters – how did you encourage them to become more independent?

MP: First and foremost, I know the one who loves me even more than my wife is my daughter. Because the daughter first and foremost thinks about the father – second, the mother [I look at Kakenya, confused. She nods – it’s true, in Maasai, the father is who the daughter looks up to the most]…You don’t want a daughter dependent on a man who is a lousy fellow and doesn’t care because that will destroy their life. It is very important for girls to be educated enough to decide what they want. [If they are educated and] They get married, they can decide how many children they can have – when they are uneducated, they do not have that thing to decide. Within 10 years, a girl married at the age of 13 or 14 – by the age of 25 she has 10 children.

K: What about the other side of the equation – if empowered women continue to be paired with men who do not take responsibility – do you see any need for actions to empower men in different ways to be more responsible towards the women they marry, and towards their families?

MP: The only way to empower a man is through education, – he has to decide his life for himself. It’s very difficult to tell these fellows what to do. When an educated girl reaches a level like her [points to Kakenya], you can’t mess with her – it is difficult to mess around with her. That’s why our [educated] daughters end up marrying people from other communities – white people or other African[s] outside their clan.

Then, they take away all their knowledge to another community. So it seems kind of pointless to educate her and then she goes away to America forever [Kakenya interjects, “I’m not going away to America forever!” laughing]. So there are good and bad about it. Good because she’s better as a human being – a person – bad because the community will lose her in terms of support.

——-

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

The MP’s daughters are successful university students and professionals; it is clear he has prioritized their education regardless of gender. And, in addition to his unusual and commendable support of girls education and women’s rights, I detected the line of patriarchy in some of his responses. His notions of how a woman’s education level would affect her household – she would keep a cleaner house, have healthy, educated children; but where is the mention of her own life? Her career choices? He mentions only that she would be more discerning in choosing a husband and having a say in how many children she birthed. In reference to Kakenya, he regards her acquisition of a car and a house in America as evidence of her success. But I hesitate to draw much attention to these comments; Mr. Konchella is helping Kakenya, his own daughters, and many other girls who benefit from the schools he is helping to build. Isn’t that enough? [This is a real question]

I found the eloquent MP less prepared for my question regarding the responsibilities of men. He seemed convinced that women’s choices could be transformed by education, but Maasai men – they are an immovable force. And, in the end, he seemed to imply the lack of acceptance some men demonstrate towards women is not the issue. And Mr. Konchella isn’t to be singled out for this: it is the predominant opinion of most men I’ve met in Kenya. Mr. Konchella’s resolution to my question was that these educated women just marry men outside of their tribe; but is change going to continue in the community if women can only find men who respect their empowerment outside of the Maasai?

This is where I continue to get stuck when I see girls and women’s empowerment programs that are thriving. I wonder, how are the boys doing, the husbands? Are they recognizing women as equals, as capable of earning a living or making important family decisions? The answer is complicated. For instance, some of Kakenya’s most committed and trustworthy supporters in Kenya are men. At the same time, the majority of Kenyan women I meet have struggled enormously with gender discrimination from the men at work and at home. I hold to the notion that, without men’s willingness to accept women as competent peers, girls education will only afford a girl a better future if her father, brother, or pre-selected husband says so.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Kilgoris, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Aug 7th, 2009